Rainbows, hand-painted by children and posted on the front windows of homes across the land, became one of the enduring images of the coronavirus pandemic. They symbolised hope and solidarity, their cheerful colours a morale-booster for all. Nature’s meteorological spectrum of vibrant hues also served as a different form of inspiration, enthusing jewellery designers to look at mother earth’s broad palette of gemstones and piling them all together into rainbow-coloured jewels.

Jewellery is currently going through a joyful period of fancy-coloured sapphires, tourmalines, and beryl of almost every hue as well of course as the spectacular-coloured diamonds with yellows and browns emerging as new favourites. However, colour does slip in and out of fashion. We might be whipped up about bright colours today, but in the Roaring Twenties the Art Deco aesthetic was very monochromatic with diamonds, pearls and onyx punctuated by a beautiful emerald or ruby.

Fashions in jewellery are also influenced by new gem discoveries. Diamonds reigned supreme over high jewellery in the late Victorian-Belle Epoque era following the discoveries of new sources in South Africa. The saturated blue aquamarines found in Brazil at the turn of the century made a perfect marriage in jewellery with diamonds, while an exhibition of Ceylon sapphires given to Edward VII in 1875 sparked a trend for sapphire jewellery in the 1890s.

In 1903 Tiffany introduced kunzite, a purplish pink gemstone found in California and named it after their chief gemmologist George Frederick Kunz. A few years later another pink stone appeared in their collections, morganite, an orange-pink beryl named after the American financier and philanthropist J. P. Morgan, which prompted a period of pinkish-hued jewellery.

In the 1960s tanzanite, a blue-violet gemstone, was discovered in the foothills of Kilimanjaro in Tanzania (hence its name) and became an overnight success with jewellers for its unusual vivid hue and clarity. In 1974 the deep green garnet tsavorite from Kenya added a rich new shade of green to the palette of emeralds, peridots, and jade. Then came the highly prized Paraiba tourmaline, the glowing neon turquoise gemstone discovered in 1989 in the Paraiba region of Brazil. Such is its rarity (although there have been subsequent discoveries in Nigeria and Mozambique) and therefore high value, Paraiba tourmalines are showcased in cocktail rings and earrings.

One hundred years ago jewellery was in the thrall of diamonds and colourless stones like rock crystal. Cartier had been exploring the exoticism of the Persian and Egyptian style in the 1910s inspired by Diaghilev’s Ballet Russe. This pre-dated the 1922 discovery of Tutankhamen’s tomb which sparked a craze for the colour combinations used in Egyptian antiquity of turquoise and lapis lazuli. However, Cartier’s graphic groupings of baguette-cut diamonds, moonstone, pearl and black onyx with colour pops of emerald, jade and rubies started appearing in the early 1920s and went on to define the hugely influential Art Deco era.

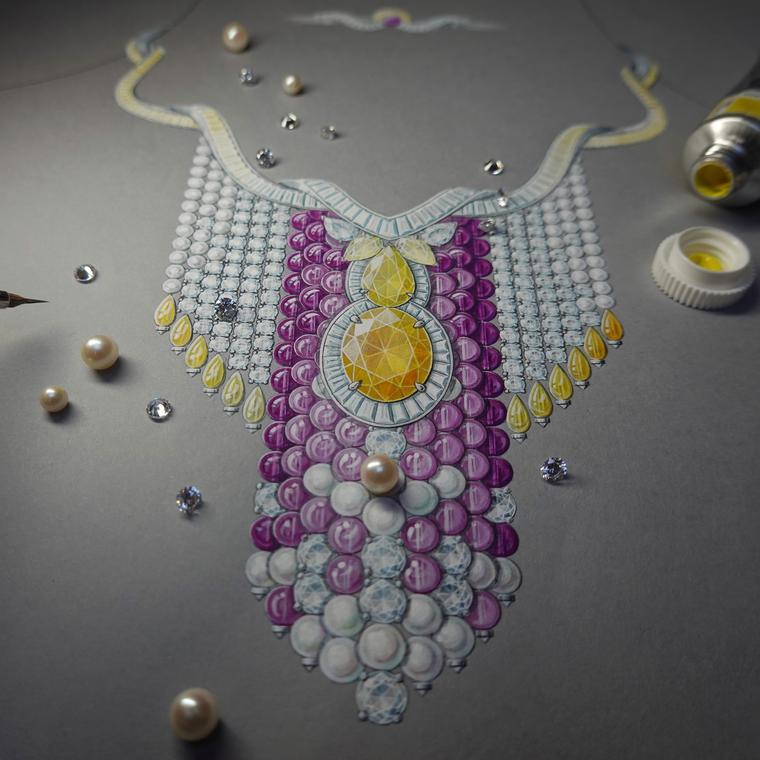

This was an immensely creative period for the maison as Jacques Cartier had been travelling in India and brought back beautifully carved emeralds, sapphires and rubies which were set with diamonds and onyx on platinum, creating one of their famous signature styles Tutti Frutti of the late 1920s. India proved a huge influence on Boucheron, which is still evident in collections today. They, like Cartier and Van Cleef & Arpels, received many commissions from India’s Maharajahs to re-set their precious gems in the European style.

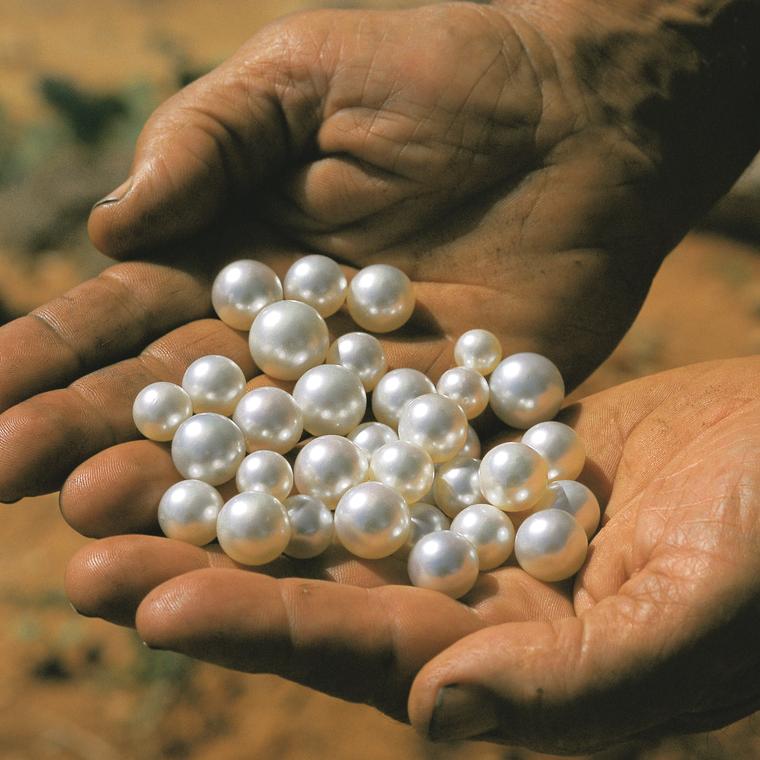

By the late 1930s Cartier and Van Cleef & Arpels were slipping away from the cool graphic black and white juxtaposition of Art Deco design and introducing yellow gold and warm coloured gemstones like citrines alongside the more precious rubies and sapphires. Jewellery got more colourful and naturalistic. Coloured gemstones inspired floral sprays and the enchanting ballerina pins designed by Van Cleef & Arpels in the 1940s. By day women wore strings of pearls, but for evening by the early 1950s diamonds were back in fashion as classic monochromatic floral and lace design necklaces created by both French maisons and the New York jewellers like Harry Winston.

To this point Bulgari had been following the French aesthetic with floral displays of yellow and cognac diamonds but within the decade they were breaking away, experimenting with striking colour combinations for chromatic effect. They began using smooth cabochon cuts for the triumvirate of red, green and blue, and voluminous shapes, but by the mid-Sixties were exploring a broader palette of shades like amethyst and turquoise for bib necklaces, adding coral, citrine, jasper and more colours for statement necklaces in the early 1970s.

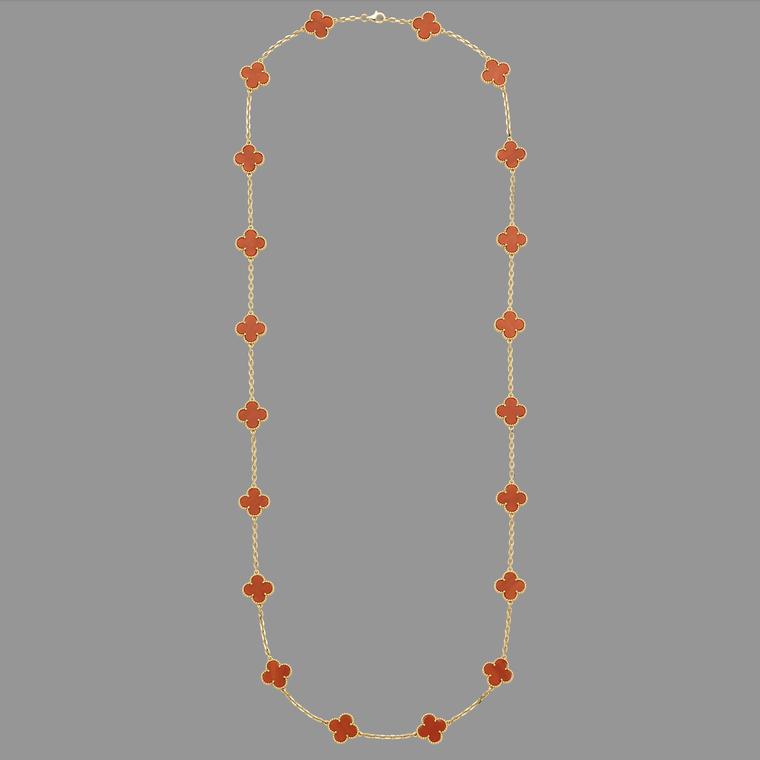

In 1968, Van Cleef & Arpels launched its emblematic Alhambra design, a collection of fine jewellery with a quatrefoil motif filled variously with hardstones such as carnelian, lapis lazuli, coral, agate and onyx. Various other hardstones were added during the 1970s like malachite and tiger’s eye. Simple sautoirs and big pendant necklaces set with semi-precious stones dominated fashion during the decade but by the 1980s trends had got a good deal flashier with yellow gold, big pearls and bold colourful precious gems making a statement.

Inevitably after the financial crisis in the late 1980s there was a kickback against such ostentatious displays and modern minimalism with silver, white gold and small diamonds dominated the early 1990s – jewellery became very discreet. At the same time talismanic semi-precious stones (smooth to the touch rather than faceted), opals and quartz crystals were being assembled in fine jewellery pendants and bracelets to accessorise the boho vintage fashion trend.

Nevertheless, diamonds bounced back: the rise of hip hop music and influential rappers like Puff Daddy (as he was then called) were demonstrating a predilection for “bling” by the time of the millennium and with it breaking taboos. Suddenly diamonds in white gold settings were seen as ice cool and accessible to anyone with the means.

The Italian brand Pomellato, meanwhile, was exploring what it called “new precious” stones, incorporating aquamarine, tourmaline, chrysoprase, spinels and demantoid garnet into their delectably coloured jewellery, culminating in the launch of their signature Nudo ring in 2001.

Although diamonds remain a dominant force in jewellery design from engagement rings to tennis bracelets and chandelier earrings, colour has become increasingly important in the designers’ repertoire with multi-coloured sapphires, tourmalines, tsavorites, spinels, chrysoberyl, opals and a library of less well-known gemstones inspiring the jewellery palette today.