Setting the stage for a revival of Elizabethan jewellery is a celebration of William Shakespeare’s legacy. While the UK gears up to commemorate the 400th anniversary of the renowned playwright’s death with myriad festivals, tours and productions, jewellery historians and consummate collectors continue to swoon over the antique jewellery of this time.

One example can be seen at the V&A Museum in London. Here, one can get a glimpse at some of the famed jewels that were commissioned for, and by, Queen Elizabeth I, as well as other pieces of the age in which she ruled. Elizabethan/English Renaissance jewellery is extremely hard to find on the open market, and when authentic pieces are procured by shops, auction houses and dealers, the prices reflect their rarity.

The jewels of what was known as the English Renaissance arrived somewhat later than those of the Italian Renaissance, but the styles are similar and affected much of European jewellery design. It was also a time when all of the arts flourished in England. The reign of Queen Elizabeth I (1558-1603) was known as the golden age in English history. It was a time that inspired international expansion and naval triumph over the Spanish. This time period also represented major accomplishments in poetry, music and literature. The era is most famous for theatre, as William Shakespeare and Christopher Marlowe, among others, wrote and produced plays that imbued new life into England’s productions. Writers such as John Milton, John Donne and Katherine Philips are also of this period, and Queen Elizabeth I herself was fluent in classical Greek and wrote her own poetry. It is interesting to note that Shakespeare had access to Greek and Latin classics in his small grammar school in the town of Stratford-upon-Avon.

The Queen was reported to love the theatre and had more playhouses built in England to accommodate productions. In addition to this affinity, she also possessed a great passion for jewellery. In almost all of her portraits she is wearing gems in pendants, earrings and hair ornaments, or in jewellery placed strategically on her gowns. She favoured baroque pearls, vivid coloured gemstones, certain allegorical animals and portrait miniatures, which set the fashions of her court as well as the upper class in England - as this was the only class that could afford to wear jewellery.

She had portrait miniatures of herself created for her courtiers as gifts, while her subjects commissioned others to prove loyalty to her. These pendants were crafted into intricately carved cameo portraits or exquisitely painted miniatures. Nicholas Hilliard was the leading miniaturist of his day and was the goldsmith and limner to the Queen. These pieces were decorated on both sides with gold work, various motifs, enamel and gems; while the rings were set with hard stone cameos and were much simpler so could be produced more easily and in larger quantities.

During this period, three-dimensional pendants, intricately designed ultra-long chains, and baroque pearl jewellery all reigned. Pendants included all types of animals, ships and cupids, as well as a host of other symbolic motifs, and sometimes more than one at a time, telling little stories of their own. These were often enamelled and highly detailed. Chains were also exquisitely crafted with foliate motifs and enamel on both sides of the patterned links. Since the collars were high and there was minimal bare skin, jewels were designed to pop from the rich fabrics of the fashions, worn either over the collars, in the hair, or sewn into dresses.

Rings were popular as well, and although carved cameo and signet rings were worn, three types were most desirable during this time and continued on through the 18th and early 19th centuries in different variations. It is not surprising that one of these styles, posy, or poetry, rings engraved with verse and declarations of love, friendship and religious messages were described in at least two of Shakespeare’s plays. Posy rings date back to the 14th century, with early 16th century versions featuring bands engraved with flowers and other patterns of love, faith and loyalty, and inscribed with a motto. Later, posies were of simpler design - plain bands inscribed with sayings engraved on the inside.

The posy rings in Shakespeare’s plays sometimes heightened the comedy or tragedy. Hamlet asks, “Is this a prologue or the posy of a ring?” And Ophelia answers, “Tis brief my lord, as a women’s love.” In The Merchant of Venice, the drama is played up with a posy ring, which is inscribed with “Love me, and leave me not” given to Gratiano by Nerissa, which Gratiano swears never to give away, yet does. And so they quarrel. “About a hoop of gold, a paltry ring. That she did give me, whose posy was for all the world like cutler’s poetry upon a knife, ‘Love me and leave me not’”. To which Nerissa replies, “What talk you of the posy or the value? You swore to me when I did give it you that you would wear it till your hour of death.”

Fede Gimmel rings, from the Latin Mani Fede, meaning hands in faith, with two clasped or closed hands on twin hoops, which swivel open revealing a heart, were another style that dated back to earlier times but were popular throughout this period and continued into the 19th century. The styles that were being designed throughout Europe during the 16th century were enamelled and held hearts. The earlier Italian Renaissance jewellery styles featured two hoops, each with a precious stone and enamelling all around, with a range of motifs that represented birth, love and death, and versions of these styles could be seen during the early part of the 16th century. Shakespeare, whether knowingly or not, alludes to these rings when, in The Tempest, Ferdinand says, “Here is my hand” and Miranda replies, “And mine with my heart in it.”

Other rings of the times were continuations of the Italian Renaissance, with stones set into quatrefoils and enamelled on the sides and the top in high carat gold. Rings in portraits and often in real life were worn on every finger.

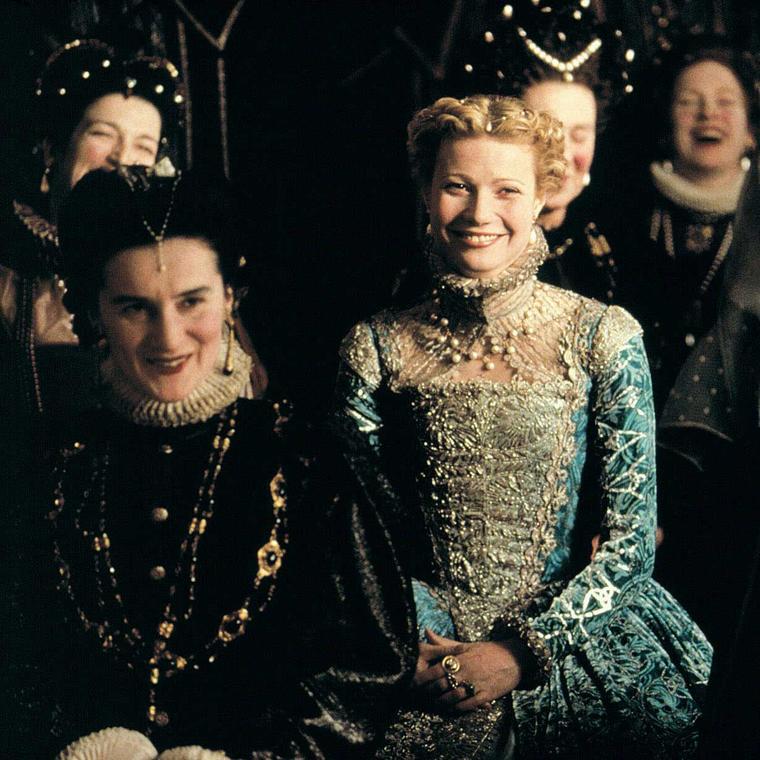

Films such as Shakespeare in Love, Elizabeth, and Elizabeth: The Golden Age offer wonderful and entertaining reference points if you want a quick fix. For a more extensive look into the world of Elizabethan jewellery and Shakespeare’s plays, I suggest you make not haste and plan an outing to the V&A Museum and attend some of the productions of the masterful plays that will be produced in the UK throughout the spring.