At first glance, there is no greater contradiction than a jeweller seeking inspiration in impermanence. High jewellery is built to last forever; Japanese aesthetics, from wabi-sabi to ikebana, celebrate the fleeting, the imperfect, the transient. In her latest Carte Blanche collection for Boucheron, Claire Choisne seizes this paradox head-on. Impermanence unfolds as six floral compositions, fading from transparency to darkness, where a tulip, a thistle or a poppy are captured in borosilicate glass, bio-resin or even Vantablack. “Nature is disappearing and as a jeweller I can make it eternal,” Choisne told The Jewellery Editor in Paris — distilling a philosophy that turns the fragility of life into enduring ornament.

To understand Impermanence, one must first look to Japan. Wabi-sabi, rooted in Zen Buddhism, embraces imperfection, impermanence and incompleteness, finding beauty in weathering, asymmetry and transience. Ikebana, the art of flower arranging, privileges space as much as form, valuing each stage of a bloom’s life — from bud to full flower to withering. Unlike Western traditions, which often idealise symmetry and permanence, Japanese aesthetics invite contemplation of time’s passage. By drawing on these philosophies, Choisne connects high jewellery to a cultural tradition that sees fragility not as a flaw but as a source of beauty.

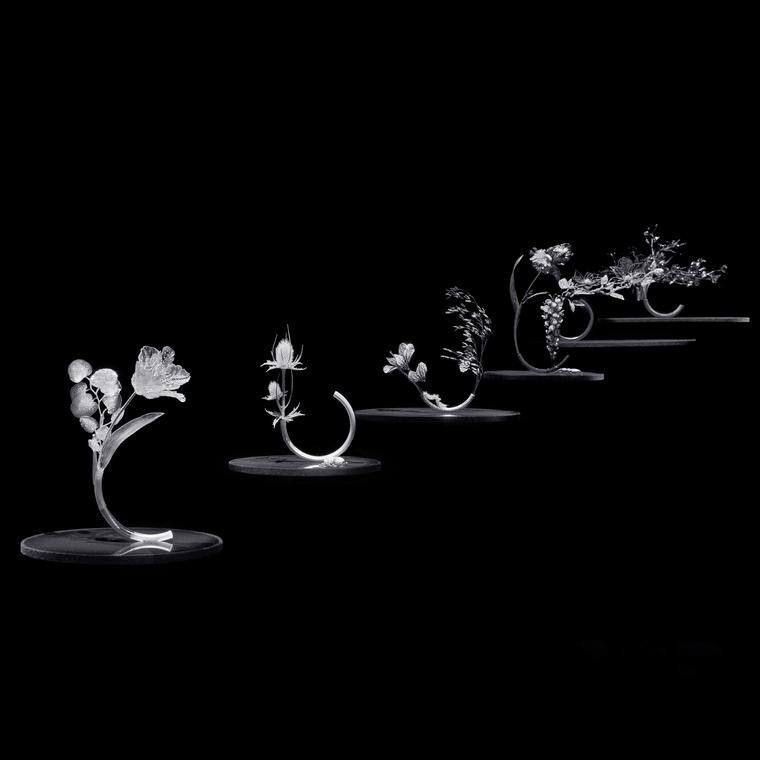

The six compositions are deliberately numbered in reverse, from No. 6 to No. 1, charting a path from light to darkness. This reversal acts like a countdown, each number marking nature’s gradual retreat until it is extinguished in the void of Vantablack.

Composition No. 6 introduces a tulip, a eucalyptus branch and a dragonfly, appearing weightless in borosilicate glass. This material, more commonly used for scientific instruments, allowed Boucheron’s artisans to sculpt petals just two millimetres thick, with stamens mobile around the pistil. The dragonfly’s wings overlay sapphire glass onto mother-of-pearl to mimic natural iridescence.

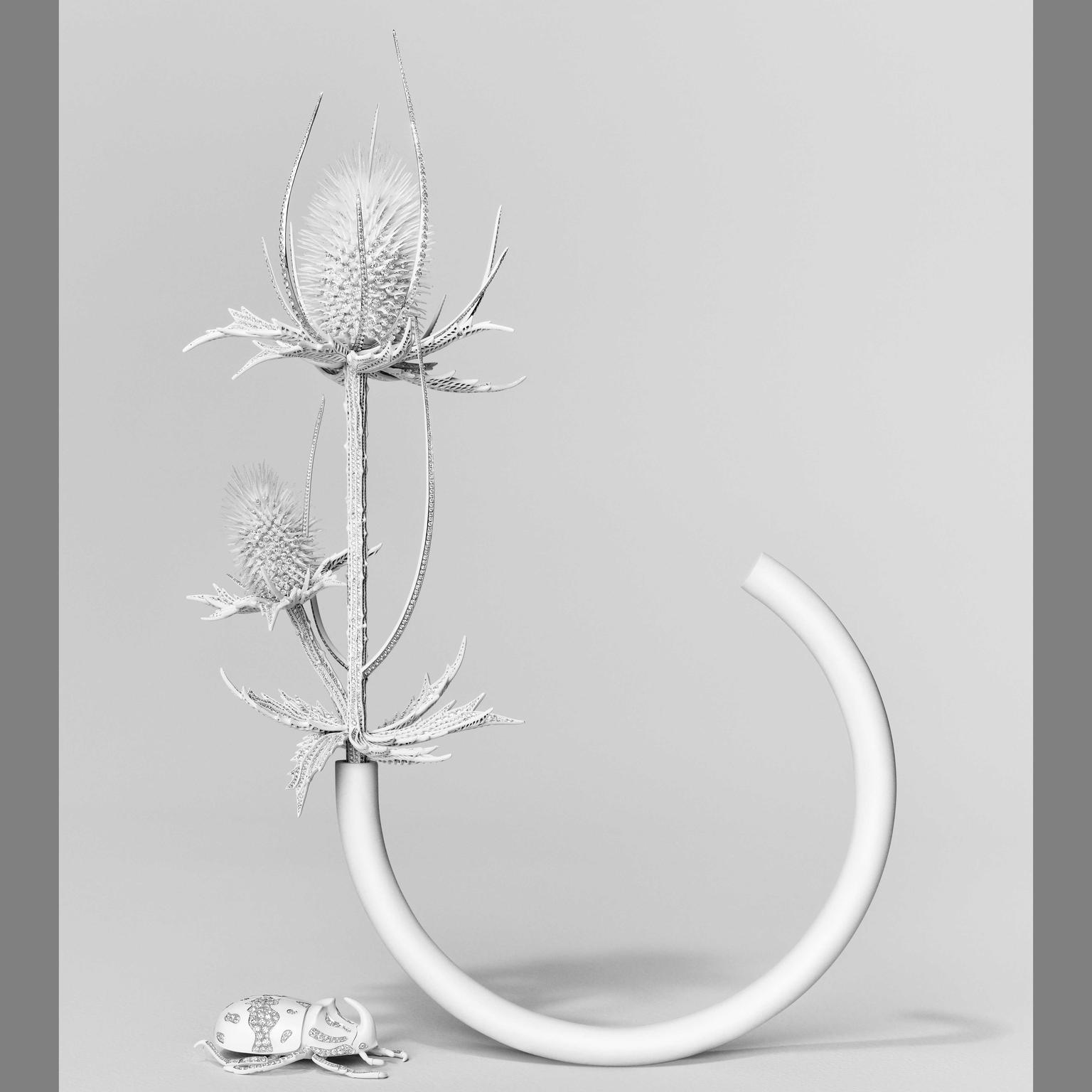

Composition No. 5 turns to the thistle, recreated in plant-based resin using ultra-high-resolution 3D printing. The fragile blooms are set with over 600 diamonds using a pioneering “couture” technique, where stones are literally sewn into the resin. A rhinoceros beetle in white gold and ceramic hovers nearby.

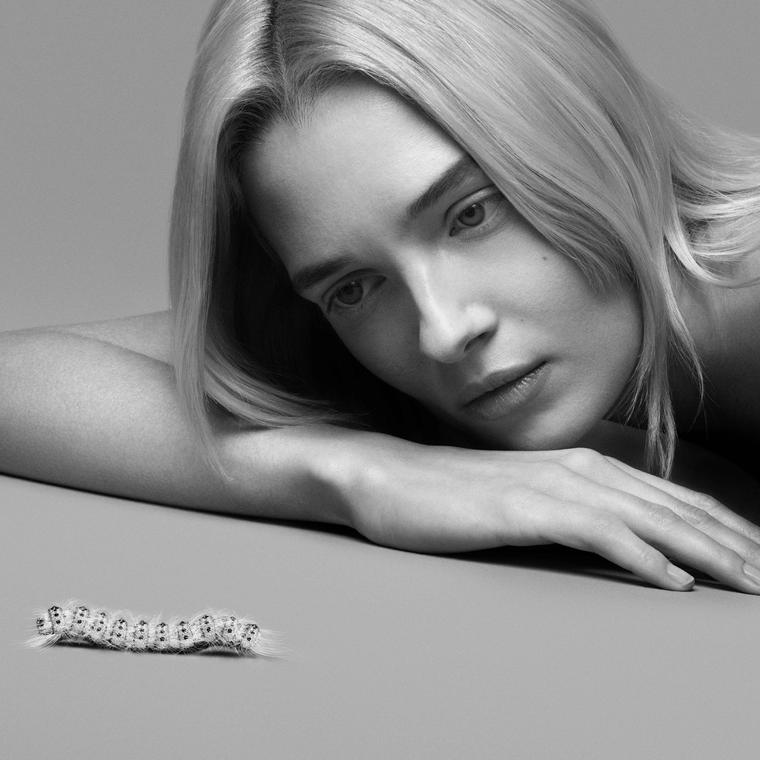

Composition No. 4 brings together cyclamen and oat, joined by a butterfly and a caterpillar with hairs made from cut paintbrush fibres. Nearly 700 rose-cut diamonds, set with almost invisible metal, turn the cyclamen into a shimmering stained-glass effect. Choisne recalled how, during development, one of her agendas simply read “caterpillar.” The memory made her smile. “I loved it,” she said, “I loved designing this collection.” The anecdote reveals the delight that underpins even the most philosophical of her creations.

Composition No. 3 plunges deeper into shadow with iris and wisteria. The wisteria comb, made from aluminium and titanium, weighs only 150 grams despite its volume. A stag beetle, sculpted in titanium and lacquer, anchors the arrangement.

Composition No. 2 presents a magnolia branch scanned from life, its skeletal remains fashioned in aluminium and diamonds. The piece can be adjusted into a necklace or tiara, echoing the spirit of Frida Kahlo. A stick insect clings delicately to the branch.

The final tableau, Composition No. 1, is consumed by blackness. Sweet peas and a poppy are rendered in onyx, aventurine glass and titanium, their petals coated with Vantablack, one of the darkest substances ever created. Developed in 2014 by Surrey NanoSystems in the UK, the name comes from “Vertically Aligned NanoTube Arrays” and “black.” The coating is formed of billions of microscopic carbon tubes that trap incoming light instead of reflecting it, absorbing 99.965 percent of it and converting it into heat. The result is an eerie optical effect where shape and volume seem to disappear, leaving only emptiness. Originally engineered to improve telescopes and scientific instruments by eliminating stray light, Vantablack has since fascinated artists and designers for its ability to turn objects into voids. Light seems to vanish into matter, leaving only a constellation of diamonds set on the pistils. “For me, they are the stars of the universe,” said Choisne, describing the final stage of nature’s fading.

Boucheron’s dialogue with Japan is not new. In the late 19th century, the maison embraced Japonisme, adorning jewels with cherry blossoms and dragonflies. What sets Impermanence apart is that Choisne does not borrow motifs but embraces philosophies. The result is not imitation but translation: impermanence, fragility and asymmetry expressed in diamonds, glass, resin and sand.

More than a collection, Impermanence is a meditation in precious form. Through wabi-sabi and ikebana, Choisne turns jewellery into a vessel of time, crystallising what is destined to fade: a tulip in glass, a thistle in resin, a poppy in Vantablack. It is a reminder that high jewellery is not only adornment but art — a medium for ideas as much as for beauty, capable of questioning permanence itself. In Impermanence, contradiction becomes creation, and even what disappears can endure.

Click here to watch our Instagram reel.