Among the rarest and most expensive type of pearl in the world, conch pearls are in demand once again thanks to the resurgence in popularity of natural pearls of all varieties and a renewed appreciation of their uniqueness. In this in-depth article you will find out everything you need to know about these precious little treasures of the sea.

What are conch pearls?

Pretty and pastel-hued, a conch pearl is a calcareous concretion produced by the Queen conch (pronounced “conk”) mollusc, which is a large, edible sea snail. Most often pink in colour and normally oval shaped, the finest examples display a wave-like “flame” structure on their surface and have a creamy, porcelain-like appearance and unique shimmer.

Unlike pearls harvested from oysters, conch pearls – like other naturally occurring pearls, including the Melo and Giant Clam – are non-nacreous, which means they are not made of nacre, the substance that gives traditional pearls their iridescent lustre. Therefore, they are not technically a pearl and are not considered to be “true pearls”, although they are still referred to as such.

The majority of pearls today are cultivated by inserting an irritant into the mollusc and managing its progress, but a conch pearl is a completely natural phenomenon, with no intervention from man.

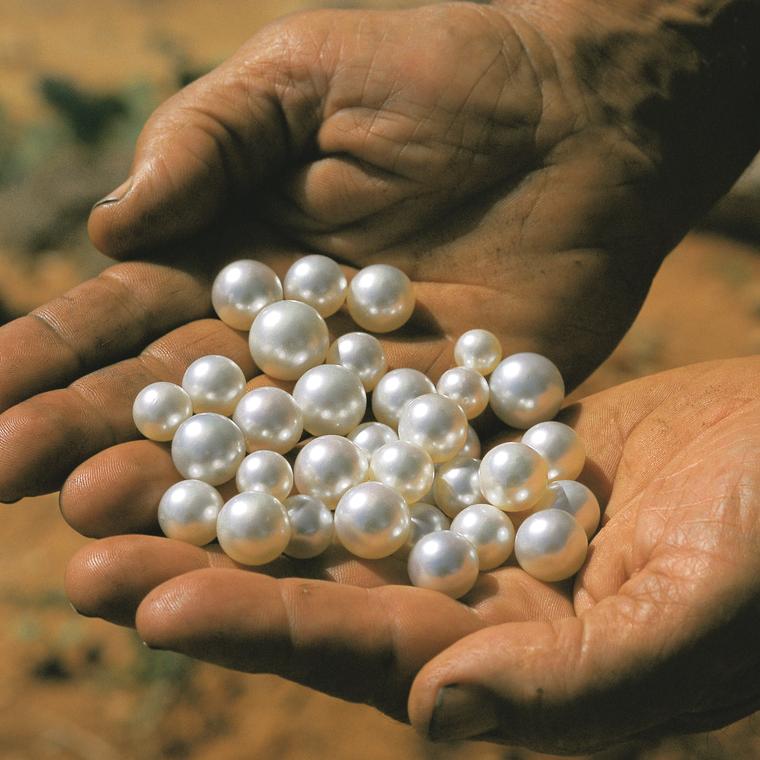

Harvested by teams of fishermen, a single, elusive conch pearl is found in every 10-15,000 shells, although less than 10% of these are gem quality. This, together with its unusual colour, makes the conch pearl extremely desirable.

How are conch pearls formed?

It is believed that a conch pearl is formed when an irritant, often a broken bit of shell, enters the Queen conch, around which a calcareous concentration forms. These concentric layers of fibrous crystals build up around the irritant, in the same way as kidney stones grow in humans.

Unlike oysters, which can be prized open to reveal the exact location of a pearl, no-one knows precisely where conch pearls are formed because of the elaborate whorled structure of a conch shell. Grown inside a pearl sac in the orange mantle of the Queen conch, they are normally found at the same time as the meat is cut out of the shell.

Where are conch pearls found?

Found in large groups of up to 200, Queen conches live among beds of sea grass in the warm tropical waters of the Caribbean, from the Yucatán all the way up to Bermuda.

Conch pearls are a beautiful by-product of the fishing industry in this region. Caught primarily for its meat, the Queen conch is eaten throughout the Caribbean and the US, raw in salads or cooked in local delicacies such as chowders and fritters.

Overfishing in many of the locations in which the Queen conch is found has forced all but three conch-producing countries to ban fishing to protect populations, which it is predicted will not recover for decades. This means fewer conch pearls are coming to market.

At one time, Queen conches were also found off the coast of Florida, where it is now illegal to fish them.

Why are conch pearls so rare?

In a world dominated by cultured pearls, natural pearls, formed without human intervention, come with the “rare” tag that makes them infinitely more desirable. Just like gemstones, which are more valuable if they are sold in their natural, untreated state, the exclusivity of conch pearls is partly down to the fact that they are 100% as nature intended. However, there are other factors that contribute to their rarity.

Traditional nacreous pearls, such as South Sea or Tahitian pearls, are formed in bivalve molluscs, which have two shells, hinged in the middle. A conch pearl is formed in a gastropod mollusc, which has a single spirally constructed shell consisting of many chambers.

All pearls are formed when an irritant is trapped within the mollusc, which the pearl grows around, regardless of whether it is nacreous or non-nacreous, like the conch pearl. Because of the make-up of a Queen conch shell, with just a single entrance, it is much more difficult for an irritant to become embedded inside, which is why it has proved almost impossible to cultivate them.

With the probability of finding a conch pearl about one in 10,000 thousand, and with less than a one in 10 chance that the pearl will be gem quality, conch pearls are considered very rare indeed.

Conch pearl cultivation

There are very few recorded instances of the successful cultivation of conch pearls because of their sensitivity to traditional seeding techniques, which involves injecting an irritant into the conch.

In the 1930s, it is believed that a biological researcher named La Place Bostwick may indeed have cultivated conch pearls, as detailed in several articles at the time, but no more was ever reported on the matter and no definitive evidence was ever given to prove it.

More recently, in 2009, Florida Atlantic University’s Harbor Branch Oceanographic Institute successfully cultivated approximately 200 conch pearls. Following this achievement, in 2012 it was reported that scientists at the FAU were planning on seeding a large batch of conch. Dr Megan Davis at Harbor Branch continues to work on this project, but coming up with a definitive result that could potentially be marketable continues to prove elusive.

Conch pearl meaning

Whilst there is no archaeological evidence that conch pearls were used as a form of adornment in ancient times, conch shells were symbolic to the Incas and other early civilisations, who regarded them as a mouthpiece of the gods. It is reasonable to assume, then, that conch pearls, together with other natural pearls, were used in jewellery from a very early age.

Conch pearl colours and shapes

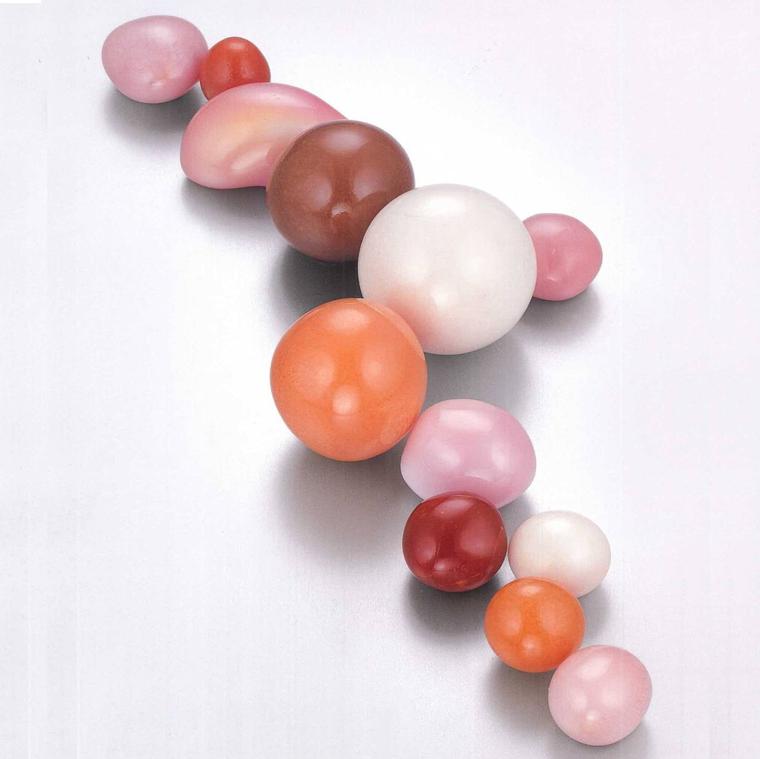

Conch pearls are found in a variety of colours, from white, beige, yellow and brown to golden and many different shades of pink – so many that they were regularly referred to as “pink pearls” in the 19th century.

Brown is the most commonly observed colour for a conch pearl. However, because they are often discarded by fishermen, they come up for sale less frequently, which may give buyers a skewed view of their prevalence.

Chocolate-coloured conch pearls are the rarest, followed by white, while conch pearls that are yellowish brown are often referred to as golden. The most valuable conch pearls by a long way are the pinks. These range from very pale pink to salmon pink and even a pink that is so intense it is referred to as red. Most coveted of all are the brilliant pink conch pearls, which burn with a chatoyancy that looks like a flame.

The colour of a conch pearl may be determined by the colour of the Queen conch’s shell, which can change at different stages in its life, or what it is eating. For example, yellow conch pearls are often found in young conches as some, but not most, have yellow lips. Because there is no hard and fast rule, it is safer to say that a conch pearl’s colour reflects the colour of the shell at its most recent time of growth.

Gem-quality conch pearls are often oval, which lends itself perfectly to jewellery, but they are found in all kinds of shapes, from baroque to rounded. Very rarely are they perfectly spherical. A perfectly symmetrical oval is the most desirable.

Conch pearl size

It is unusual to find a conch pearl that exceeds 2-3mm, and one that weighs more than 10 carats is considered exceptional.

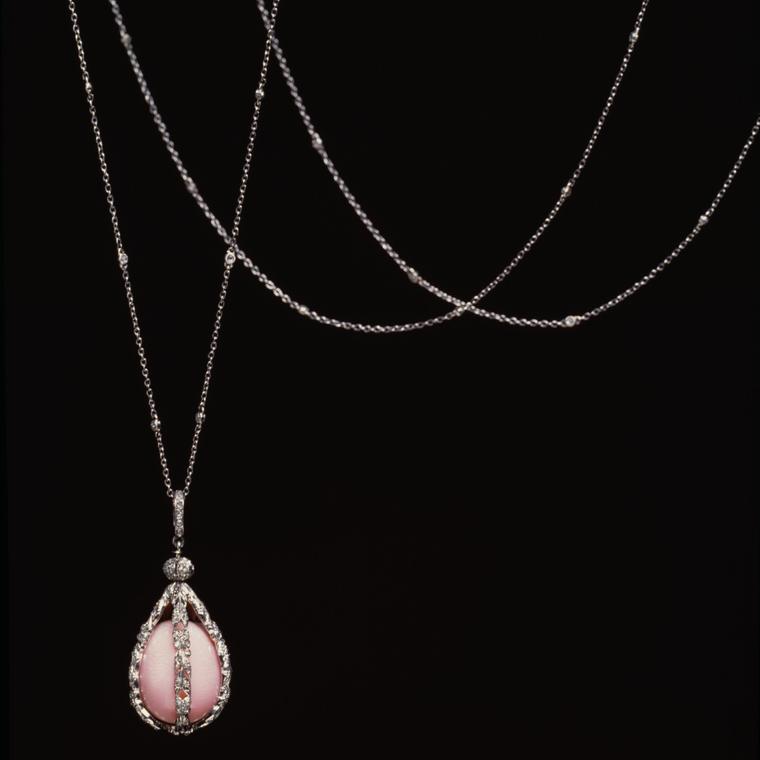

In 1905, Henry Walters, founder of the Walters Art Museum in Baltimore, bought the sautoir necklace, above, from Tiffany & Co. for his niece Laura Delano, the centrepiece of which is a large pink conch pearl weighing 3.64g or, in gem terms, 23.50 carats – one of the largest examples in the world at the time.

Typical of Edwardian-era design, the necklace features a hinged cage that opens, allowing you to take a closer look at the pearl inside. The necklace was gifted back to Walters in 1977 and, ever since, it has been housed at the Walters Art Museum.

In 2015, the Swiss jeweller Boghossian created the necklace below, set with 32 colour-matched pink conch pearls, including one incredibly rare drop-shaped pearl weighing 23.97 carats.

The largest conch pearl in the world

One of the biggest known conch pearls in history is a whopping 45 carats. Pear-shaped and reddish pink in colour, it was set into a necklace by New York jeweller Harry Winston in the 1980s, which sold after Liz Taylor modelled it on the front cover of Good Housekeeping magazine around 1990. It changed hands at auction several times after that, but its whereabouts now is unknown.

During my research for this article I spoke to leading conch pearl expert Sue Hendrickson. She told me that she knows of three pearls in existence that are over 100 carats, including a pale pink baroque conch pearl set into a brooch designed by the Genevan jeweller Georges Ruiz.

Jeremy Morris, managing director of David Morris, an exclusive jeweller on London’s Bond Street, is currently in possession of one of the largest conch pearls available to buy today, weighing 44.55 carats. “It’s the perfect baroque pink conch pearl,” he says proudly, “which I have hand-set in pink micro diamonds.”

Conch pearl flame structure

All conch pearls display a unique chatoyancy that resembles a flame under magnification, creating a delicate wavy pattern of lighter and darker areas on the surface of the pearl. This striking silk-like effect is caused by the formation of calcite microcrystalline fibres in concentric layers just below the surface of the pearl.

In the highest-quality conch pearls, this is visible to the naked eye. Conch pearls with a readily visible flame structure, like the one set into the brooch below by Cindy Chao, command a higher price and are the most sought after.

Conch pearl value

A combination of size, shape, colour and flame effect determines the value of a conch pearl. “Prices vary wildly and have increased rapidly for the rarest pearls,” says Sue Hendrickson. “Therefore, people are reluctant to quote them. Excellent pearls today can cost as much as $15,000 per carat and more, but those are the exceptionally rare ones. Top-grade conch pearls are more typically around $4,000-$7,000 per carat and nice, but not necessarily perfect, pearls around $2,000-$3,000.”

The resurgence of conch pearls – why now?

Prior to the introduction of the cultured pearl in the 1920s, natural pearls were as highly prized as rubies, emeralds and diamonds. Once cultured varieties flooded the market, however, pearls lost their exclusive tag.

Today, cultured pearls are farmed from the UAE to French Polynesia and sold throughout the world, and it is their ubiquity that has lowered the value of all but the finest examples of them.

Conch pearls, on the other hand, are formed completely naturally and only found in very specific areas in the Caribbean. So far, no cultured conch pearls have come to market, making them exceedingly rare.

They may lack the iridescence and pleasing symmetry of nacreous pearls, but the natural, organic beauty of conch pearls is no less spectacular, and this is a trend that we are seeing throughout the world of gemstones. Buyers are hunting out the unique and unusual, from little-known gem varieties, unusual-coloured stones and baroque pearls in weird and wonderful shapes. The desire for uniqueness among jewellery buyers has never been stronger, and conch pearls fit the bill perfectly.

Famous conch pearl owners and collectors

Elizabeth Taylor may have donned a suite of conch pearl jewels back in 1990 when she modelled a necklace and earrings for Harry Winston, but Brad Pitt is the highest-profile celebrity to have purchased a conch pearl. The Hollywood actor is reported to have bought one from the Italian jeweller Damiani for his then-wife Jennifer Aniston.

Manuel Marcial de Gomar of Emeralds International in Key West is a self-confessed conch pearl aficionado whose interest was piqued when he was offered one in exchange for half-a-dozen lobsters while living on the San Bernardo Islands in Colombia’s Caribbean Sea. He is now considered a global authority on queen conch pearls and, in 2009, launched a definitive Conch Pearl Color Description Guide within the industry to help dealers and appraisers better grade conch pearls.

Palaeontologist and marine archaeologist Sue Hendrickson is a name that crops up time and time again when reading about conch pearls. Best known for her discovery of the largest and most complete skeleton of a T-rex in South Dakota in 1990, she has one of the biggest private collections of conch pearls in the world, started in the 1970s, just as the conch fishing industry was taking off, and sourced directly from conch fishermen in the Caribbean.

At the time, conch pearls were rarely being used in jewellery and had no commercial value, but all that changed in the 1980s when one of Hendrickson’s competitors sold a handful of them to Harry Winston, the largest of which was the 45-carat conch pearl mentioned previously. Suddenly, their gemstone status was being recognised by the big jewellery houses.

“I have a few thousand conch pearls in my collection,” says Hendrickson. “I still actively acquire them - I buy and sell conch pearls, and keep some of them. I collected my first conch shell more than 60 years ago, when I was five years old, and years later I supported myself by diving for shells, cleaning them and selling them to shell collectors.”

With lots of fishing data collected over the years, she hoped to write a book on the subject, but she decided it would be hard to sell something heavy on fishing, biology and data, so she decided that the main focus should be on jewellery instead. The result is the beautifully presented coffee table book The Pink Pearl.

“Interest in conch pearls is gradually rising,” says Hendrickson. “I have loaned to exhibitions in the past and some of my pearls have been acquired by various museums for their collections. The best conch pearl collection that I know of is the one held by the National Museum of Qatar.”

Conch pearls in jewellery design

The former general director of Japanese pearl giant Mikimoto, Ryo Yamaguci, is credited with creating a demand for conch pearls. Assisted by Sue Hendrickson, who sold close to 8,000 gems to Mikimoto over their first decade of working together, he decided that the premier dealer in cultured pearls should also carry natural pearls. Yamaguci started out with conch pearls in 1987 but Mikimoto soon carried other types of natural pearls also.

“Before that there were few buyers in Europe,” explains Hendrickson. “Those that were familiar with conch pearls knew them from antique jewellery, and American pearl dealers were not aware of them at all. The dedication Mikimoto put in to promoting natural pearls created the market that exists today.”

Mikimoto continues to launch new jewels in its conch pearl collection each year, including the necklace pictured above, and, unsurprisingly, awareness of the gem is at its highest in Japan.

The history of conch pearls in jewellery design stretches back centuries, however. “In the 1800s, the shells were used as ballast in sailing ships, thus they were fished in large quantities for their shells,” says Hendrickson. “And of course you need large quantities of shells to be able to find the pearls.” There is evidence that they were worn decoratively in the 1850s-60s, and Tiffany’s Blue Book from 1894 contained loose pearls, including pink Conch pearls from Florida and the West Indies.

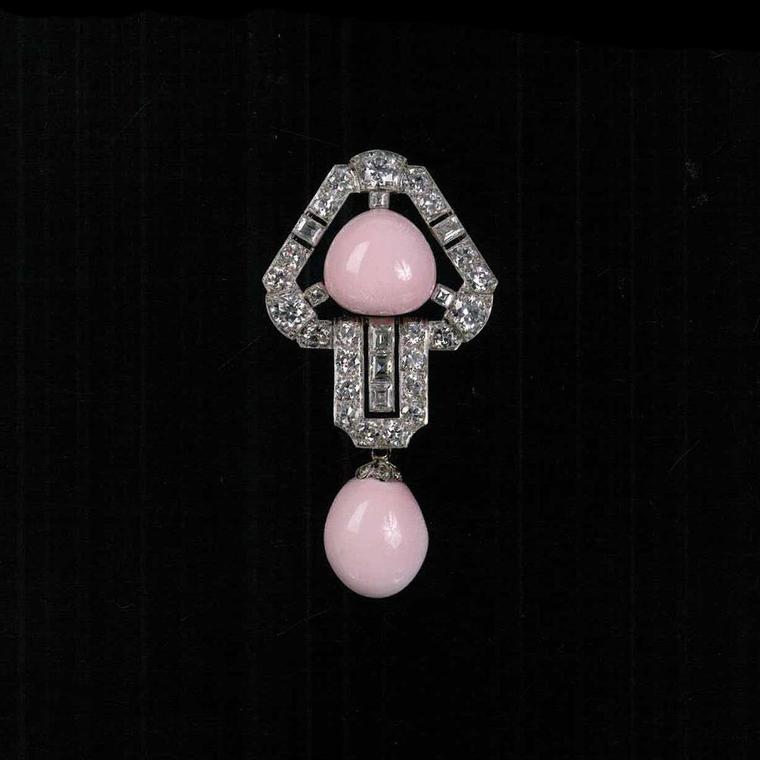

Their popularity peaked in the late-Victorian and Edwardian eras, when they were referred to as “pink pearls”, which is attributed to the decline in the availability of natural pearls.

One prominent example from the era is the Queen Mary Conch Pearl Brooch, which formed part of “The Allure of Pearls” Exhibition at the National Museum of Natural History at the Smithsonian Institution in 2005. Featuring two natural pink conch pearls weighing 24.9 and 28.1 carats, the brooch was most likely designed by the Crown Jeweller to the royal family at the time, Garrard & Co.

Another example of a classic Edwardian design is the Tiffany & Co. pendant featured earlier, but not all the conch pearl jewellery of the era was set with large and valuable gems, and smaller conch pearls were not overlooked. Their organic shape was perfectly suited to the naturalistic Art Nouveau jewels of the period, and they were regularly used to depict buds and stamens in romantic floral designs.

The popularity of conch pearls was short-lived. In 1893, Kokichi Mikimoto succeeded in culturing the world’s first semi-spherical pearl and, by the 1920s, the market was flooded with affordable pearls in a wide variety of colours, shapes and sizes, signalling the death knell for the labour-intensive natural pearl fishing industry. At the same time, the non-symmetrical appearance of conch pearls was at odds with the stark geometric aesthetic of the Art Deco era, leading to a dramatic decline in the use of conch pearls in jewellery design.

Thankfully, their use didn’t die out altogether, as this stunning conch pearl, enamel and diamond bracelet, designed by Cartier in the late 1920s, proves. From the personal collection of Queen Victoria Eugenia of Spain, it sold for 3,274,500 CHF at Sotheby’s Geneva in 2012.

Conch pearl jewellery in the 21st century

Jeremy Morris, Managing Director of David Morris, is also responsible for dreaming up many of the jewels that come out of this high-end jewellery house. As principal designer, he is in a unique position in that he not only sources the top-quality stones for which the house is famed but can decide precisely what to do with them.

He remembers the moment, more than a decade ago in the Bahamas, that he was compelled to hunt out conch pearls. “I have happy memories of my first visit to Harbour Island with a group of friends and my wife Erin, who was heavily pregnant at the time, and that's where my passion for conch pearls really took off. The island is a sandy pink jewel in the middle of the Caribbean, accessible only by scary prop planes from Nassau. Everyone was excited about enjoying the local flavours, conch fritters, conch stew and raw conch salad, against the beautiful backdrop of Caribbean sunsets and sugar-sand beaches. It was then that I felt inspired to set out on a mission to find the elusive conch pearl.”

It didn’t prove easy. “Erin and I were captivated by the mystifying tale of these pearls, and she struck up conversations with the local fishermen to find out if they had ever found a pearl inside any of the thousands of conches they fish for a living,” explains Morris. “Each and every time, the reply was no, underlining just how elusive these gems are.

“After we'd been searching for a week, one fisherman heard of our request and came to me with three conch pearls,” he continues. “The first was shaped like a tooth while the second was brown, demonstrating two of the many colours and shapes they come in. However, the last one was a perfect little bubblegum gem. My wife and I were extremely excited to finally have found this precious pearl, and the feeling of euphoria was only heightened by the knowledge that we were about to have a little girl who we could later give it to.”

Together with the rarest of rare 44.55-carat conch pearl ring featured earlier, Morris recently designed the spectacular necklace above, which is currently for sale at the jeweller’s newly opened boutique in Paris. “It was a labour of pure love as I collected these conch pearls over a seven-year period. The necklace is complemented by a pair of conch pearl and white diamond earrings. I am proud to say that we have the best selection of conch pearls on Bond Street.”

India’s Bina Goenka has created several beautiful pieces of high jewellery recently showcasing conch pearls. The cuff below is set with conch pearls in a wide variety of shapes and colours, from beige to golden to pink. Listen in as Goenka discusses the many different shades conch pearls come in:

Very few of the pearls are a perfect oval shape or pink in colour, yet this piece is still very significant. Goenka explains: “To find a good-quality pearl that is striking pink with a strong flame structure, an even shape and good size is almost impossible. Only one pearl meeting that criteria may be retrieved from 200 tonnes of shell mass. There is never any guarantee and that’s how a single good-quality conch pearl commands such a high price. When you have multiple conch pearls, it is considered a collector’s collection because to achieve that is near impossible.”

London-based jeweller Sarah Ho also has a passion for conch pearls, which she has been researching, and searching for, for the past five years. She loves them for their rarity and because each is formed as nature intended. “They are all unique and the variety of colours and shapes is so appealing,” explains Ho, whose first conch pearl creation, a pair of Couture Paradis earrings, quickly became her signature piece.

Her new Hidden Garden collection includes the spectacular Persica suite of jewels, above, set with conch pearls in many shades of pink, some of which are triangular shaped. “I look for the individual colours, from pastels to vivid pink, affectionately known as ‘tutti frutti’”, explains Ho. “The triangular conch pearls used in the Persica necklace are exceptionally rare and took me over two years to collect. This makes the Persica suite a complete one-off.”

Though pink conch pearls are most commonly seen in jewellery, other colours can also make for spectacular and highly unusual creations. In 1995, Hemmerle created the naturalistic Tarantula brooch, below. The abdomen of the venomous spider was recreated using a 111.76-carat dark-brown conch pearl – one of the largest and rarest ever found.

When to wear your conch pearl jewellery

A word of advice before you take the plunge and buy a piece of conch pearl jewellery. Known as the night gem, conch pearls are prone to fading with prolonged exposure to sunlight. So while you may be tempted to wear your conch pearls all the time, it is advisable to keep them primarily for evening or occasional wear.